- Home

- Terrie M. Williams

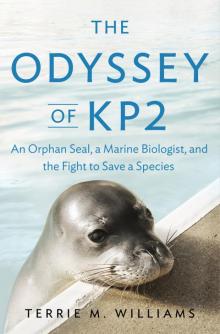

The Odyssey of KP2

The Odyssey of KP2 Read online

The Odyssey of KP2

AN ORPHAN SEAL, A MARINE BIOLOGIST, AND THE FIGHT TO SAVE A SPECIES

Terrie M. Williams

THE PENGUIN PRESS

New York

2012

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. • Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England • Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) • Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) • Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India • Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) • Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2012 by The Penguin Press,

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright © Terrie M. Williams, 2012

All rights reserved

Image credits

1, 2: David Williams (NMFS permit no. 13602-01, Terrie M. Williams)

3: Teri Rowles (NMFS permit no. 932-1905, Teri Rowles)

4: National Marine Fisheries Service

5: Terrie M. Williams

6: Patricia Sullivan

Map illustration by Meighan Cavanaugh

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Williams, Terrie M.

The odyssey of KP2 : an orphan seal, a marine biologist, and the fight to save a species / Terrie M. Williams.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-101-57229-0

1. Hawaiian monk seal—Conservation. 2. Wildlife conservation—Hawaii. 3. Wildlife rehabilitation—Hawaii. 4. Endangered species—Hawaii. 5. Williams, Terrie M. I. Title.

QL737.P64W55 2012

599.79'23—dc23 2011050415

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

To the Volunteers: the heart of the ocean

One touch of nature makes the whole world kin.

—William Shakespeare

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Map

Preface

PART I

Destiny

1.Birth

2.Explorations

3.First Steps

4.Growth

5.Discovery

6.Stolen Child

PART II

Passages

7.Journeys

8.LA Landings

9.Sealebrity

10.Mele Kalikimaka

11.Maui Wauwie

12.The Lost Seals

PART III

Survival

13.Instinct and Intelligence

14.Breath by Breath

15.Killer Appetites

16.The Social Seal

17.A Roof Above

18.Mother’s Day

19.The Hand of Man

20.Wild Waters

21.The Voice of the Ocean

22.Aloha Hoa

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Additional Reading and Resources

Index

Preface

In a violent spring downpour off the southern coast of Molokai, an outrigger canoe threatened to capsize in rough waters. Six paddlers were buffeted in the seas as they strained to reach the protective harbor in Kaunakakai. Seawater and rain poured into the canoe, mixing with the sweat of the struggling team. As dark clouds descended and with their heads bent in exertion, the paddlers soon lost their bearings. Small and exposed, only the thin shell of the craft separated them from tiger sharks patrolling the waters below.

Impending darkness and the chill of hypothermia intensified the danger, when suddenly a small bald head popped out of the water. Spiky eyebrow hairs gave the smooth gray head a comical, monkish appearance. The head floated in the distance and then sank among the waves. Before any of the paddlers could react, the young Hawaiian monk seal reappeared alongside their canoe.

“KP2!” one of the paddlers shouted. The ten-month-old monk seal had arrived at Kaunakakai Wharf several weeks before and had taken to swimming with the local children.

He was unlike any monk seal or ocean creature the residents of Molokai had ever seen. Instead of lolling on beaches like most seals, KP2 shivered with energy as he bounced around the harbor greeting people as if he were one of the family. He called to children with an enthusiastic flipper slap to the water and swam circles around their treading legs, eliciting squeals of delight. When the mother of one of the children waded into the water with a pink boogie board, the locals soon discovered that this young seal also had a unique talent. Somehow, somewhere, KP2 had learned to surf. Upon seeing the boogie board, he immediately flopped his body on top and propelled himself across the water with his hind flippers churning up a white frothy wake.

The island community was left stunned by this unusual, friendly seal. Considering him a gift from the ocean, islanders extended their highest honor to KP2, due to his obvious love of people and his surfing skill: they now called him “local.”

On this particular stormy evening the curious seal had followed the paddlers out beyond the wharf. Oblivious to the downpour, the seal attempted to board the canoe. He propped his white chin on the gunnel seeking a playmate, further destabilizing the boat.

“KP2, go home!” the paddlers yelled.

The young seal slipped dutifully back into the water, waiting for someone to follow him as they usually did. When no one jumped in, he sensed that something was different. KP2 circled the outrigger canoe once more and began to swim along the tops of the waves. The canoe team paddled in earnest to keep up with the seal, relying on his innate navigational skill. Rather than diving, which would have made his travel much easier, the seal surfed the waves and periodically turned back to watch the progress of the paddlers behind him.

Soon the jutting outline of the wharf and the lights of town were visible. Within twenty minutes the grateful team and their monk seal escort were slipping into the protected waters of Kaunakakai Harbor. With the canoe tied up and the paddlers heading home to recover from the chill, KP2 swam off. Instead of heading out to sea like a normal wild seal, he climbed onto the back transom of a docked sport-fishing boat to await the return of children in the morning and the resumption of their water play.

Unbeknownst to the snoozing seal, a series of events would soon drive a distance between him and the island people he’d befriended. He was destined to undertake a journey unlike anything experienced by his species. Years would pass, yet KP2 would never forget Hawaii or the children of the islands. They in turn would not forget him.

Most wild seals live their entire lives

without a name. Mothers easily recognize their pups just from the pitch of their cries. They communicate with each other and the rest of the ocean’s inhabitants through sounds and smells and actions. Hungry seals eagerly consume unidentified fish without formal introductions.

The anonymity of nature would suddenly change with the arrival of KP2. This remarkable seal, also lovingly known as Ho‘ailona, Smoodgey, and Mr. Hoa, inspired nicknames that were as colorful as his personality. Over the years, he would be called Butthead, Honey Boy, Fish Stealer, Little Angel, Bugger, and Elvis of the Seals, depending on his mood and his audience.

His celebrity began with his fascination with people, a behavioral anomaly among seals that would, aside from creating a remarkable extended family, repeatedly land him in trouble. Wild animals are not supposed to act this way—every fiber of undomesticated creatures urges them to escape human presence. Yet on very rare occasions, for reasons scientists cannot fully explain, an animal breaks from the pack to join us. Such was the case with KP2.

He was a wild seal, a member of an endangered species who left his own world to play in ours. Ancient Hawaiians called his kind ‘ilio holoikauaua—“the dog that runs in rough water.” I simply called him hoa—“friend.”

From the moment of his birth, he changed how many of us view our lives on this fragile planet.

PART I

Destiny

1.

Birth

My earliest aspiration, at five years old, was to grow up to be a dog. This seemed the noblest of professions, and I determined that it was only a matter of time and desire before I grew the requisite four legs and tail. My religious parents, however, had equally unlikely expectations and prayed that I’d become a Roman Catholic nun.

Sister Everista and Sister Agnes never knew their true influence on the girl known best for scraped-up knees and a love of the outdoors. Instead of civilizing the animal out of me, the stern-faced, black-habited sisters inadvertently taught me how to communicate with the “lowly creatures” of the Bible.

I found that I could perceive the nearly invisible body and eye movements comprising animal language, and predict an animal’s next move as if I were inside its mind. It wasn’t communication in a Dr. Dolittle sense; rather, I was able to “read” the local dogs, cats, foxes, squirrels, and rabbits as others might read a newspaper.

At every opportunity I’d escape the disinfected halls of the parochial schools and plunge into the wild chaos of the surrounding oak forests of the East Coast. The freedom to poke around creeks like an otter in search of frogs or to slip through thorny blackberry bushes with the liquid movement of a fox was exhilarating. My animal senses grew with time, much to the consternation of the nuns and the rest of the girls in my class. I was known somewhat disparagingly as “that girl who likes animals.” Trips to the confessional enforced by Sister Agnes with a twisting two-fingered clamp on my ear were, more often than not, to confess to the sin of having released some rescued frog, baby bird, or field mouse that had wriggled free of my pocket and crawled between the church pews. I considered the litany of Hail Marys recited on scabbed knees due penance for the creature’s salvation.

Over the years this fascination with the furred and finned evolved into a lifetime of globe-trotting in the man’s world of wildlife research. I knew that my success had less to do with raw intelligence and more with an innate ability to relate to animals. If I couldn’t be an animal, then at least I could learn to appreciate the intimate details of their daily lives by studying them. The wilderness became my cathedral. Skittish cheetahs, playful dolphins, mitten-pawed sea otters, and stoic Antarctic seals were my congregation. Dominican discipline taught me focus; Mother Superior’s demands for self-sacrifice honed an inborn skill for animal empathy.

Yet in all my wildlife encounters encompassing a lifetime of adventures, there was one major disappointment. No wild animal had ever read me in return. A Pembroke Welsh corgi named Austin, the canine member of my tiny Hawaiian ‘ohana (family), had come the closest. But when it came to the inhabitants of the woods and the oceans, animal communication had been a lonely, one-way affair. Nuns and scientific textbooks espoused that such was the nature of animals, since nonhuman creatures possessed neither souls nor intellect. Here I must say that both were mistaken. For, unexpectedly, after half a century of being the mind reader, one of them suddenly read me.

He was not the fastest, biggest, or purportedly smartest of animals; rather he was an immature, nearly blind sea mammal that had been cast out by his own species. By all rights he should have died on an isolated beach on Kauai. Like me, he began life attempting to cross physical and societal boundaries that separated humans from animals, oblivious to the impossibility. He was a boisterous surprise in a scientific career that was in danger of maturing into comfortable cynicism.

• • •

KP2 CAME INTO THE WORLD on May 1, 2008, in the usual way of seals—slippery, wet, and sliding unceremoniously from between his mother’s back flippers onto a nursing beach. With a shake of a head covered in thick black lanugo, the dark fetal fur jammies of his species, he opened his eyes to tropical tranquillity while resting a chin on scattered fragments of bleached coral. In stark contrast to the harsh, icy landings endured by his cousin Antarctic seal species, KP2’s birthplace on North Larsen’s Beach, Kauai, was one of turquoise blue water warmed by an equatorial sun. In the distance, wisps of steam rose from lush vegetation blanketing the towering pali, the mountainous peaks protecting the beach from the afternoon trade winds.

The newborn seal stretched, uncoiling flippers that had been wrapped snugly around his body in utero for the past ten months. Carried within the belly of his mother, RK22 (her National Marine Fisheries Service ID), the developing pup had submerged hundreds of feet in depth in pursuit of fish that would sustain his fetal growth. For nearly a year he had been rocked to sleep on the tides of the Hawaiian current, cradled in his mother’s womb as she swam back and forth between the islands, coral atolls, and nursing beaches.

• • •

THE QUIET OF KP2’S ENTRANCE into the world was broken within hours of his first breaths by an explosion of violent splashing immediately offshore. Raucous calls of brawling seals had awoken him and made him cry out. A throaty growl soon overwhelmed his high-pitched calls for his mother as the seal pup was attacked. In a single blow, an adult male Hawaiian monk seal nipped and rolled the newborn seal into the sand. The aggressive male left deep gouges along the tide line as he maneuvered for a second, more lethal hold on KP2’s neck—a hold that could easily have broken the pup in two.

KP2’s attacker was just as likely as not his father. Lumbering heavily on powerful front flippers and a massive chest, the four-hundred-pound male dwarfed KP2. He would have crushed the newborn had KP2 not scrambled out of the way. The male had only one goal on his testosterone-driven mind: to mate with RK22. Her pup was merely a rock-sized obstacle in his path.

Inexplicably, KP2’s mother did nothing. As her pup tried to escape among the jagged lava rocks, she watched passively. It was uncharacteristic behavior for a monk seal mother, or any seal mother, for that matter. Among the many species of pinnipeds, the collective name for the mammalian group that includes sluglike phocid seals and clownish-eared sea lions, male aggression toward newborns is not unusual. But seal mothers, even in cases in which they are outweighed three to one by full-grown males, will—even within minutes of giving birth—reproach such aggressors with teeth bared, ready to sink them into and draw blood from old, scarred chests. On nursing beaches from the tropics to the polar sea ice, pinniped mothers risk death to defend their helpless pups.

RK22 showed no such courage against her pup’s aggressor. Rather, she ignored the ruckus as KP2 was mauled, seemingly irritated by the disturbance to her afternoon nap. Confirming her indifference, RK22 followed the brutish male and another male companion into the water, leaving her ruffled offspring aband

oned and suckling on beach rocks for comfort.

• • •

“RRRAUGHH,” KP2 CALLED desperately for his mother. His second day of life was not going much better than the first, and would end just as tumultuously. With hunger overtaking KP2’s fear of further attack, he began to call loudly for his mother and her milk. Unlike the charming chirp of sea otter pups or the high-pitched squealing whistles of dolphin calves, KP2’s cry was a distinctive rumbling “rrrraaughhhh.”

Each rough-edged bawl of the pup contained a vocal signature that could be distinguished by his mother from any other seal’s call, had there been others around. An unbreakable mother-pup bond existed between KP2 and RK22 that transcended her lack of interest. A permanent connection, stronger than the pull of the moon on the tides, had formed deep within the instinctual parts of their brains the instant he had wriggled free from her placenta. Nose to nose and whisker to whisker, they had sniffed and vocalized in pinniped recognition of each other’s earthly existence in those first moments. Their mutual greeting in the shared instant of birth had sealed their genetic knot. She could not deny that he was biologically tied to her or that his calls were beckoning her.

When KP2’s mother finally responded to his cries, she was accompanied by the large, pugnacious male who trailed persistently behind her. Again KP2 was attacked. But this time, it was his own mother who turned on him. With an aggression typically reserved for territorial fights, she took his head into her mouth and bit down. If she had wanted, she could have killed her offspring instantly by puncturing his skull with her sharp canine teeth. Instead, she grabbed the struggling pup in her mouth, shook him from side to side like a dog with a wet dish towel, and spat him out on the ground. KP2 rolled in a limp bundle of matted fur and sand, his uncoordinated flippers flailing in the ocean debris of the high-tide line.

More flustered than hurt, the pup struggled to regain his footing. Disoriented and battered, KP2 was not sure which way to crawl. So he hunkered down in the sand where he had landed.

The Odyssey of KP2

The Odyssey of KP2